I had never experienced such strong resentment towards my parents as I did the day I entered my new home after marrying at twenty-one. Why did my mother think that a large house would automatically bring happiness to her daughter? Did she not realize I was moving to a remote village in Kerala, where the community appeared frozen in time?

“Business runs in the family. They deal in textiles, and wealth flows into the household thanks to a savvy businessman like Mr. Murthy,” my father said, admiring my future father-in-law.

“So, why do they choose to live in that secluded village?” I couldn’t help asking. It seemed to have irritated my grandmother.

“It’s their family home. Mr. Murthy bought it outright from his siblings.” She asserted in a sharp tone,

I couldn’t help but wonder how my grandmother had managed to acquire such extensive information.

“They have more than enough money. Our Aarti will live like royalty,” my mother and grandmother continued to praise the family after their visit to the prospective groom’s home.

I envisioned a husband from a bustling city working in a prestigious office. Yet my parents were completely enchanted by this marriage proposal.

Murali, the potential groom, held a degree in science, so what was he doing in the textile market? My parents seemed oblivious to the disconnect between education and occupation. They insisted that no corporate position could rival the income Murali earned from his business.

The wealth of the Murthy family clearly clouded my parents’ judgment, and my father considered their wedding demands completely reasonable.

“We need a Godrej cupboard with a safety locker for your daughter. It will go in her room upstairs,” Mrs. Suguna, the mother-in-law, insisted.

“A motorbike so your son-in-law can get home quickly from the textile market, which is just 4 kilometers away,” Mr. Murthy added with a grin.

In my innocence, I thought they wanted the Godrej cupboard because of its safety features, not realizing it was really a matter of status in the eyes of the villagers. I also mistakenly believed they wanted their son to return home swiftly to take his new wife out, hence the request for a motorbike. At that time, I was blissfully unaware that in that village, a husband and wife going for a simple walk together was looked down upon. Pillion riding a bike with her husband was akin to a sin committed by the wife.

The Murthys were indeed smart. They tactfully put forth their demands, making it look quite obvious.

The requests made to Cheeru* were quite clear: “Prepare 101 of each item, which consists of three sweets and two savoury snacks, ensuring that the sweets are crafted with pure ghee.” With a confident smirk, the mother-in-law skillfully pointed out her shrewdness.

I had previously met Murali and his parents just once, during their brief visit to Madras before the wedding. It was customary for me to refrain from visiting my future home ahead of the marriage. Little did I know, anticipation brewed back in the village, where many were eager to meet the daughter-in-law from the city. In our community, marriages typically happen among relatives, with families closely residing together. Thus, a bride from outside the family and urban upbringing was a rarity.

For those curious about my reasons for agreeing to this marriage, I can attest that sometimes destiny has a way of guiding our paths.

In my last year of college, my father faced health issues that forced him into early retirement due to heart complications.

“Appa’s health is declining. He wishes to see you wed as soon as possible.” One day, my mother held my hands tightly, tears in her eyes, explaining her emotional plea. What could I do? Her tears tugged at my heart.

That’s when the proposal materialized—thanks to Kitcha Mama, a distant relative.

“This family is quite affluent,” he enthusiastically asserted.

I informed my mother of my plans to pursue a Bachelor of Education after the wedding. Although I possessed skills in painting, stitching, embroidery, and crocheting, teaching mathematics in school was my lifelong ambition.

“Absolutely, why not?” Kitcha Mama responded affirmatively. He wasn’t the one going to decide my future, you see!

My mother reassured me, “There’s no need to worry,” when I expressed my concerns about relocating to an unfamiliar place.

My worries were dismissed as trivial. The excitement surrounding the proposal drowned out my voice, compelling me to accept the plan.

A week after completing my final graduation exam, I found myself seated beside Murali at the wedding altar.

Then, I was in the car with my husband, wearing a saree that felt like it added an extra two kilograms to my weight— a token from my in-laws meant to showcase their ‘generosity’ to the entire village. We were on our way to his ‘palace.’

I found it quite entertaining to see the villagers peering at me from their homes, observing me like an outsider through the iron bars known as ‘Ayee’ and from the front area termed ‘Thinnai.’

What my grandmother called a palace caught my attention. Compared to my well-maintained three-bedroom apartment in Madras, this place felt vast yet rather rundown.

As I walked past the Thinnai, I came across a small space that was meant to serve as a drawing room, though it barely qualified for the title. The few chairs, adorned with cushions, looked as if they hadn’t seen a cleaning since their purchase. The cushion covers seemed to mock the family’s business.

Pushing aside the discomfort rising in my stomach, I ventured into the next sizable room. To my left lay a deep rectangular basin, which I assumed was for washing hands after meals. The patches of moss scattered about indicated it hadn’t been cleaned in ages. The environment felt hectic, with the sound of a television blaring from a raised platform on the right. A few men and women were transfixed by what looked like a Malayalam soap opera.

“Get coffee, ladoos, and murukku for everyone. They’re here to see you. More guests will be arriving soon.” That was the voice of my father-in-law’s elder sister, Kamakshi Athai.

Kamakshi Athai had been disowned by her husband shortly after their marriage nearly forty years ago, and in those days, remarriage was frowned upon. She found refuge with her brother’s family.

Following Kamakshi Athai’s guidance, I navigated through what resembled a basketball court, referred to as the house’s ‘Koodam,’ toward the kitchen. I passed another room with a dining table and a fridge that represented a rather poor excuse for a dining area.

The kitchen looked like a chaotic cricket field.

How was a new bride expected to know where to find the ladoos and murukkus or where to locate the milk and coffee decoction? Thankfully, divine assistance came in the form of Kaveri, the housemaid, who appeared to be in her early sixties.

“Molle,” she called to me with warmth. This is the pot for your coffee. ” She smiled, showing a set of tobacco-stained teeth. While it was somewhat off-putting, I needed her help to locate the food tins.

I confidently presented the beautifully arranged plates in succession—one filled with sweet and savory delights and the other carrying steel glasses of coffee, expecting compliments. However, no one, not even my husband, acknowledged the effort.

Almost immediately, I heard Mrs. Suguna grumbling about the coffee being too sweet. “Is this coffee or payasam?” she exclaimed.

“You should’ve asked how much sugar we prefer; your father-in-law likes his coffee less sweet,” Kamakshi Athai replied.

“Murthy, if you can’t handle such sugary coffee, just leave it,” she directed toward her brother, who had already emptied his glass.

“Wasn’t it hot? You like your coffee hot, but it seemed cold; you finished it so fast,” Mrs. Suguna remarked, wrinkling her face. To emphasize her point, she took a sip from her own glass. It likely burned her tongue, as she hadn’t noticed her husband using a davera* to cool his drink while she distracted the television audience, encouraging them to sample the murukku.

I couldn’t help but notice the sarcastic twist of my brother-in-law Gopu’s lips and the knowing smirk of his sister Mala as our older relatives critiqued my efforts. Murali remained unfazed by the unfolding spectacle.

In that moment, it became clear to me that the skills I had honed would go entirely unacknowledged in an environment like this.

As the days went by, a steady stream of guests arrived, expecting me to always have dosa batter ready, no matter the hour, and to prepare meals for more than just my immediate family. While visitors praised the generosity of the Murthy family, none bothered to mention the meals or recognize the effort that went into planning the menu. If there was extra food, Kaveri simply took it home.

Before long, I realized that Mrs. Suguna was keen to offload her responsibilities and relax, yet she continued to linger in the kitchen with Kamakshi Athai, scrutinizing my every move.

Murali remained the quiet observer, eating silently and refraining from either praise or criticism, while the rest busily found fault with the food.

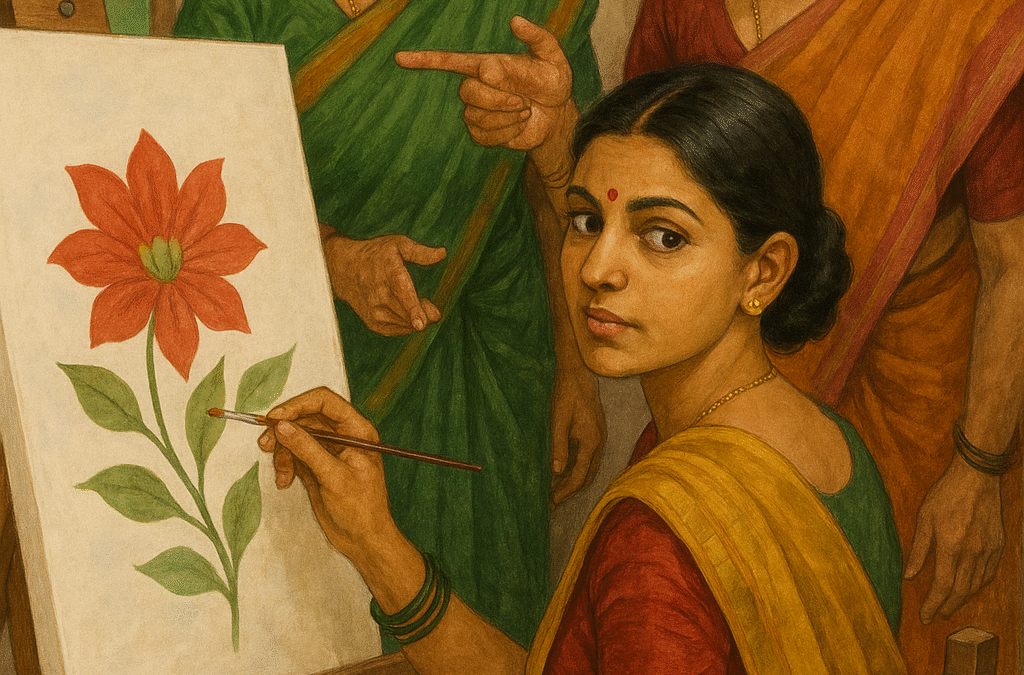

I valued Murali’s silence, though he never stood up for me. For instance, when Kaveri forgot to bring in the clothes from the line and it started to rain, Kamakshi Athai and Mrs. Suguna stormed into my room to chastise me while I was painting a beautiful picture of Lord Krishna.

“You can find time for this but not for the clothes?” Kamakshi scoffed.

“And don’t get paint on the walls!” Mrs. Suguna complained, dismissing my efforts and muttering about spending money on “pointless endeavors.”

Just then, Murali entered, saying nothing to defend me or critique them. They didn’t even acknowledge my painting.

To deepen my distress, a couple of weeks after my arrival, Mrs. Suguna confronted me as I stepped out of the bath. “When is your monthly period due?” she demanded, catching me off guard with her directness. I stumbled over my words as she insisted I couldn’t be in the kitchen during my period, suggesting that city girls lacked basic values. “I hope you don’t get your periods,” I overheard her muttering. The implication that she expected me to be pregnant sooner rattled me.

I had already shared my desire to delay motherhood with Murali, who still hadn’t addressed my plans for teacher training after graduation. “I’ll talk to Appa after your results,” he said, indicating that Mr. Murthy would ultimately steer my future. I sensed that he and Mrs. Suguna wouldn’t support my pursuit of further education since they were already discussing babies, shattering my aspirations of becoming a teacher.

When my period finally arrived, the entire village was informed through Mrs. Suguna because I was confined to a corner of the Thinnai for three days, exposed for all passers-by to see. I had to endure their traditions.

Nevertheless, life must go on. My father, frail and with a weak heart, wasn’t capable of coping with my tales of sorrow; besides, my parents had determined that Mr. Murthy’s family was exemplary. Discussing my feelings with Murali would be like attempting to convey music to someone who cannot hear.

The neighbors, more than Mrs. Suguna, were undoubtedly curious about my three days of vigil on the Thinnai the following month.

“No good news?” teased Meenakshi Mami from next door. Kamakshi Athai and Mrs. Suguna exchanged glances of disapproval as if some disaster had occurred.

“Does Murali know what he’s supposed to do?” another woman added, half-suppressed giggles escaping her lips.

To say I was shocked would be an understatement. To spare my husband any embarrassment, I had to mentally prepare for motherhood, even though I felt emotionally ill-equipped for it.

You can only imagine the trials I faced during my pregnancy. I was discouraged from discussing my bouts of nausea.

The months leading up to my parents taking me home for delivery were agonizing. Alongside my nausea and other pregnancy-related discomforts, the constant nagging from Mrs. Suguna and Kamakshi Athai drained my appetite and affected my weight. The doctor voiced concerns regarding my weight loss.

“We’re doing everything we can. While we’re preparing an array of dishes, she hardly touches any of them,” Mrs. Suguna exaggerated her woes. Although I couldn’t dispute that they were making special meals, the bulk of them were for their daughter, Mala, who would soon be departing for her new life after marriage.

As my parents and I walked home following the marriage, a wave of relief washed over me. My son was born on a bright Sunday afternoon.

When my father relayed the news, Kamakshi Athai insisted, “His name will be Murthy. ” This was my moment to assert myself. I appreciate your input, Athai, but my son will be named Rudra. I’ve made my decision.” I made my stance clear.

On the other end, I could hear a cacophony of voices. My mother gently nudged me to avoid confrontation. “It’s traditional to name the firstborn son after his paternal grandfather,” she whispered. “I find this tradition illogical. My son will be Rudra,” I reasserted, holding the phone firmly. For days afterward, I marveled at my newfound resolve to stand up for my beliefs.

That day illustrated to me the power of determination and composure in realizing my wishes. I learned that it’s possible to maintain my calm while articulating my thoughts respectfully, ensuring that outcomes reflect my desires instead of yielding to others’ expectations or customs.

After returning five months later, I noted the heavy atmosphere; the family seemed less enthusiastic about welcoming guests eager to meet Rudra. I suspected their displeasure stemmed from my decision to name my son without their input, coupled with a shift in my attitude.

However, Murali revealed deeper issues affecting the family, which contributed to the sombre mood.

Mala was facing significant conflicts with her in-laws and had also been diagnosed with infertility. Her in-laws and her husband, Ramu, blamed the Murthys for not disclosing this issue before marrying her into their affluent family.

Meanwhile, Gopu expressed his feelings for his cousin Ramya, the daughter of Mrs. Suguna’s elder brother, despite their historically tense relationship. Unlike Murali, Gopu was assertive and adept at handling disputes, standing firm against his parents regarding the marriage.

Then, Mr. and Mrs. Suguna received some shocking news.

Gopu insisted on dividing the family business between the two brothers and proposed selling their large house. He straightforwardly demanded his share of the funds to build his own home.

The once-stately house, despite its wear, would soon change hands.

Once Ramu received his share, he ceased complaining about Mala’s inability to conceive, effectively ending that conversation.

After their pride and selfishness were humbled, the Murthy couple and Kamakshi Athai retreated into isolation. Moving in with Gopu was off the table, and considering their advancing age, living independently while taking care of Athai would be increasingly challenging. They had no option other than to move with us.

We lived in a separate bungalow in a colony. This neighborhood felt warm and welcoming, with everyone respecting each other’s privacy, a stark contrast to the prying nature of the village community.

I found my true passion here, where I invested my energy in starting a class. My dream of creating my own space was gradually becoming a reality. My home was adorned with my artwork and paintings, while embroidered cushion covers and curtains showcased my love for stitching and needlework. Guests frequently commended my enthusiasm.

We lived harmoniously under one roof, each respecting the other’s space—a balance I had long sought since my marriage.

Rudra ultimately pursued a career in engineering. By the time he enrolled in college and graduated, our village had evolved into a bustling town. Although the textile industry flourished, Rudra had no intention of following in his father’s footsteps. Shortly after graduation, he received an exceptional job offer in Bengaluru.

Kamakshi Athai passed away at a venerable age, just days before Rudra’s wedding to Suchitra, a colleague of his. Over the years, perspectives shifted significantly. Neither Mr. Murthy nor Mrs. Suguna appeared concerned when they learned that Suchitra hailed from a different community.

Murali, as always, bore no ill will toward anyone.

After the wedding, my daughter-in-law stayed with us for a week before departing for her honeymoon and heading back to Bengaluru.

During this time, Suchitra noticed a little girl in the living room watching television.

“Aunty, who is this girl?” she asked.

“That’s the maid’s daughter; she accompanies her mother here,” I replied, sensing Suchitra’s lack of appreciation.

“And she watches television?” Suchitra snapped. Addressing the girl, she instructed, “Go sit with your mother,” before turning off the TV.

“People like them just exploit others. I’m glad we’re planning to move to the US. We’ll have to handle everything on our own there—no servants to depend on,” she stated while heading to her room.

I exchanged looks with Murali, both of us pondering the implications of her comments. Rudra was indeed planning to relocate to the US, though we had not been privy to the specifics.

How things have evolved! There was a time when Murali needed his father’s consent just to take me to the movies.

As Suchitra and Rudra retreated to their room, I couldn’t help but admire the bright, spirited girl.

I was juggling a lot and didn’t have time to contemplate Rudra’s decision, which he made with input from his wife. As parents, we see things differently; years ago, we were kids with a completely different outlook. I let out a deep sigh.

The next evening, Mr. Murthy and Mrs. Suguna sat on the porch, savoring the sunset.

“I could really cherish a cup of coffee,” Mrs. Suguna said, making a move to get up and brew it.

I looked at the clock; it was 6:25 PM. ‘Coffee this late? Dinner’s just an hour away!’ That would have been Mrs. Suguna’s reaction years ago if the roles were reversed.

I encouraged her to stay put. “Amma, I’ll handle the coffee for both of you,” I assured her as I headed to the kitchen. While I was making the coffee, Suchitra walked in.

‘I have a splitting headache. Can I get some coffee too?” She asked gently.

“Your head is splitting because your stomach must be empty. It is almost five hours since you had anything. Come, sit, let me make some dosas for you,” I said handing her a cup of coffee.

“But dinner is hardly an hour away,” She dragged.

“One should eat when one feels hungry. What use it is allowing the stomach to remain empty and stick to timings?”

With gratitude filled in her eyes, the girl looked at me, as I recollected an incident years ago when I had walked into the kitchen one evening feeling hungry. I had removed the dosa batter from the fridge, meaning to make a couple of dosas for myself, when Mrs Suguna came sprinting to the kitchen.

“In a couple of hours, we will be having dinner,” she snarled. “What is the idea of wasting the batter now?.” She snatched the batter vessel rudely from my hand and placed it back in the fridge. All this happened in the very presence of Murali, but as usual, he turned a deaf year to his mother’s hollering.

One can eat only when one feels hungry. Why did I quietly shed tears without retaliating? The question surfaced many times but without any reply.

I smiled as I saw Suchitra relishing the Dosas with chutney, and soon Rudra joined her.

“Sorry, ma, we are troubling you, but genuinely hungry.” He grinned patting his stomach.

“Can I have a couple of Dosas? ” Murali said, and I burst into a peal of laughter.

“Where were you all these years?” I asked.

“I was here only,” he grinned, “but I found my voice only now. You have been a leveller in this family. I should have stood by you long before, sorry.” His words brought a smile to my face.

“Ask Amma and Appa if they, too, would like some Dosas,” I said and watched Murali move towards the porch.

I really wouldn’t mind preparing it for them, too!

THIS STORY HAS FEATURED N AN ANTHOLOGY BY “TMYS” HAVING STORIES ON LEVELLERS